December 24, 2024

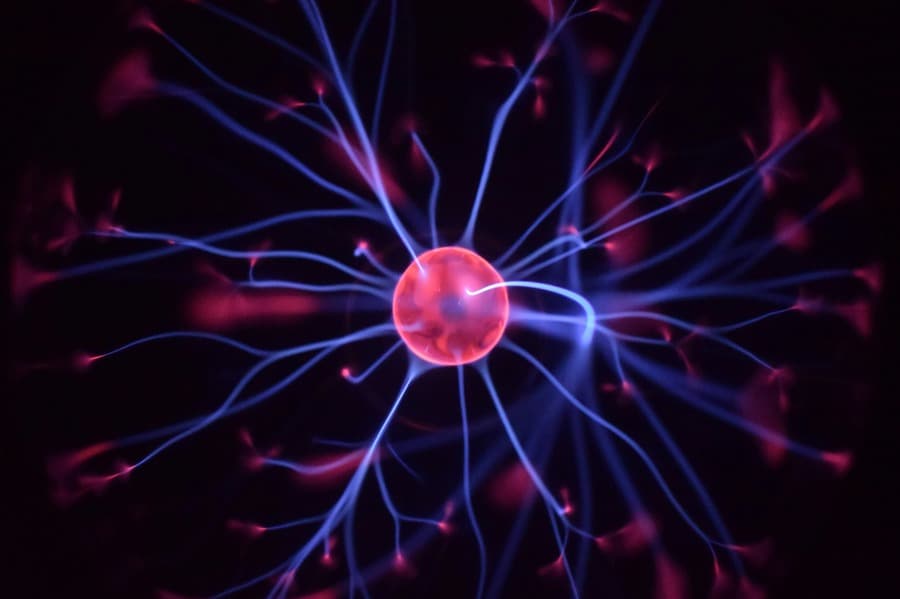

The Role of Neural Pathways

Article Navigation: Quick Access to Sections

Tinnitus, often described as a phantom ringing or buzzing in the ears, is a condition deeply rooted in the brain’s neural pathways. Recent advancements in neuroscience reveal how these pathways contribute to the perception of phantom sounds, offering new hope for innovative treatments based on understanding the brain's role in tinnitus.

Understanding Tinnitus Beyond the Ear: Introducing Neural Pathways

Tinnitus is frequently misunderstood as merely an ear problem. However, current scientific understanding emphasizes that it is often a complex condition fundamentally involving the brain’s auditory processing system and associated tinnitus neural pathways. By understanding how the brain can sometimes misinterpret silence or altered sensory input as sound, we can better address this challenging phenomenon. This article takes a deep dive into the tinnitus neuroscience, highlighting the critical roles of neuroplasticity, hyperactive neural feedback loops, and emotional processing centers.

Tinnitus: A Symptom Reflecting Underlying Changes

It's crucial to recognize that tinnitus is not a disease in itself, but rather a symptom—an indication of an underlying condition or change within the auditory system or the brain. These underlying conditions can range widely, from common issues like age-related hearing loss (presbycusis) or noise-induced hearing damage, to ear infections, medication side effects, or sometimes more complex issues like traumatic brain injuries or certain neurological disorders.

The Auditory System's Complexity: More Than Just Ears

The journey of sound perception involves far more than just the ears. It relies on an intricate network of nerves and specialized brain structures working in concert to process auditory information. Sound waves entering the ear are converted into electrical signals, travel along the auditory nerve, and pass through multiple processing stages in the brainstem and midbrain before reaching the auditory cortex for conscious perception. When this sophisticated network is disrupted—often starting with reduced or altered input from the ears—the brain may attempt to compensate, sometimes leading to the generation or perception of tinnitus.

This phenomenon underscores that tinnitus is frequently not just an auditory issue localized to the ear, but a condition deeply embedded in the brain's complex neural activity and processing.

Key Neural Mechanisms in Tinnitus Perception

To truly grasp the brain's role in tinnitus, exploring the key neural mechanisms and specific brain regions involved is essential.

1. Auditory Processing in the Brain: From Sound to Perception

- The Normal Path of Sound: Sound waves are converted into electrical signals by the cochlea's hair cells and transmitted to the brain via the auditory nerve. These signals ascend through brainstem nuclei (like the cochlear nucleus, superior olivary complex, inferior colliculus) and the thalamus before arriving at the primary auditory cortex in the temporal lobe for processing.

- Tinnitus as Aberrant Neural Activity: In many forms of tinnitus, this pathway is disrupted, often beginning with a reduction or loss of auditory input from damaged ears. Compelling evidence suggests the brain attempts to compensate for this "deafferentation" by increasing the baseline activity or "gain" within central auditory pathways, particularly the auditory cortex. This heightened, spontaneous neural firing can be perceived as phantom sounds. Understanding this central gain theory is key to grasping the neurological basis of tinnitus.

2. Neuroplasticity: The Brain's Adaptive (and Sometimes Maladaptive) Ability

- What is Neuroplasticity? The brain possesses a remarkable ability to reorganize its structure, function, and connections in response to experience, injury, or changes in sensory input. This is known as neuroplasticity. While this adaptability is crucial for learning and recovery, it can sometimes result in maladaptive changes.

- Maladaptive Plasticity in Tinnitus: In response to the loss of specific sound frequencies due to hearing damage, the brain's auditory map can reorganize. Neurons that previously responded to the lost frequencies may become responsive to adjacent frequencies or increase their spontaneous activity. This maladaptive reorganization is believed to be a significant contributor to the generation and persistence of tinnitus sounds.

3. Altered Feedback Loops and Neural Hyperactivity

- Disrupted Inhibitory/Excitatory Balance: The auditory system relies on a delicate balance of excitatory and inhibitory neural signals and feedback mechanisms to accurately process sound and filter out noise. Damage or changes in input can disrupt these loops, potentially leading to a reduction in inhibition and consequently, hyperactivity in certain neural circuits, amplifying neural noise and worsening tinnitus.

- Auditory Gain Control: This concept relates to the brain’s "volume knob." In many tinnitus models, it's thought the brain "turns up the volume" (increases central gain) to compensate for missing peripheral input. While intended to enhance faint sounds, this often leads to excessive neural sensitivity and the perception of phantom sounds.

Brain Regions Implicated in Tinnitus Perception and Distress

Recent tinnitus research, often using advanced neuroimaging techniques like functional MRI (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET), has identified several key brain regions consistently involved in the perception and emotional experience of tinnitus:

1. The Auditory Cortex

- Role: Located in the temporal lobe, this is the brain's primary center for processing sound information.

- Findings in Tinnitus: Numerous studies show that in tinnitus patients, the auditory cortex often exhibits heightened spontaneous activity, abnormal neural synchrony, and altered tonotopic maps (the brain's frequency organization), even in complete silence.

2. The Limbic System (Emotional Brain)

- Role: Includes structures like the amygdala (fear/emotion processing) and hippocampus (memory). It governs emotions, stress responses, and memory formation.

- Connection to Tinnitus: The significant emotional responses often accompanying tinnitus (like stress and anxiety) strongly suggest involvement of the limbic system. Altered connectivity between auditory pathways and the limbic system likely explains why tinnitus can be so distressing for some individuals.

3. The Prefrontal Cortex (Executive Control)

- Role: Responsible for higher cognitive functions like attention, focus, decision-making, and emotional regulation.

- Implication in Tinnitus: Altered activity or connectivity involving the prefrontal cortex may explain why tinnitus often becomes more noticeable during quiet moments, periods of heightened stress, or when attention is directed towards it. Difficulties in filtering out the tinnitus signal may relate to prefrontal function.

4. The Thalamus (Sensory Gateway)

- Role: Acts as a crucial sensory relay station, filtering and transmitting sensory information (including auditory signals) to the cerebral cortex.

- Tinnitus Involvement: Disruptions in thalamic activity or thalamocortical feedback loops may contribute to abnormal sensory integration and the generation or maintenance of tinnitus perception.

Psychological Factors Amplifying Tinnitus via Neural Pathways

The perception and severity of tinnitus are not just determined by raw neural activity but are also deeply influenced by psychological factors mediated through brain pathways.

1. Stress and the Feedback Loop

Stress is both a common trigger for tinnitus flare-ups and a frequent consequence of living with bothersome tinnitus. Chronic stress activates the limbic system and the brain's "fight-or-flight" response (sympathetic nervous system), releasing stress hormones that can sensitize neural pathways and worsen tinnitus perception. In turn, the intrusive nature of tinnitus creates more stress, perpetuating a vicious cycle involving these interconnected neural systems.

2. Anxiety and Depression

Studies consistently show that individuals with bothersome tinnitus have higher rates of anxiety and depression. The emotional burden often stems from the perceived lack of control over the condition, fear of worsening, sleep disruption, and impact on daily life. These emotional states are processed through brain networks (involving the limbic system and prefrontal cortex) that interact with auditory pathways, potentially amplifying the perceived loudness or unpleasantness of the tinnitus.

Advances in Research: Mapping Tinnitus Neural Pathways

Functional MRI (fMRI)

- Insights: Allows scientists to observe changes in blood flow, indicating which brain areas are active during tinnitus perception or in response to specific stimuli in tinnitus patients compared to controls.

- Key Findings: Often reveals increased activity in the auditory cortex and altered connectivity patterns, particularly increased functional connectivity between the auditory cortex and emotional centers like the amygdala.

Neural Oscillations & EEG/MEG

- Studies using electroencephalography (EEG) or magnetoencephalography (MEG) have found abnormal brain wave activity (neural oscillations), particularly alterations in gamma, alpha, and delta wave patterns, linked to tinnitus perception and severity.

- Researchers are now exploring techniques like neurofeedback to train individuals to normalize these aberrant brain wave patterns.

Cutting-Edge Treatments Targeting Tinnitus Neural Pathways

Understanding the brain's role in tinnitus is directly leading to innovative treatments aimed at modulating these specific neural pathways. Explore more in our article on latest research.

1. Neuromodulation

Neuromodulation techniques aim to alter abnormal neural activity non-invasively or invasively:

- Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS): Uses targeted magnetic pulses to stimulate or inhibit activity in specific brain areas, particularly the auditory cortex or related prefrontal regions, aiming to disrupt tinnitus-related hyperactivity.

- Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS): Delivers a weak, constant electrical current via scalp electrodes to modulate the excitability of underlying brain regions.

2. Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs)

While still largely experimental for tinnitus, BCIs use advanced signal processing, often involving AI, to potentially map and modulate the specific neural circuits associated with an individual's tinnitus perception, holding promise for highly personalized future treatments.

3. Pharmacological Advances

Based on understanding neurotransmitter imbalances in tinnitus pathways, scientists are investigating drugs targeting systems like glutamate (excitatory) and GABA (inhibitory) to reduce hyperactivity in the auditory cortex and other relevant brain regions.

4. Sound-Based Therapies Targeting Plasticity

Modern sound therapy approaches increasingly leverage neuroplasticity. Tailored sounds (like notched music therapy, which removes frequencies around the tinnitus pitch) are used to try and retrain the brain, reducing hyperactivity in the cortical areas corresponding to the tinnitus frequency and promoting beneficial reorganization.

Practical Tips for Managing Tinnitus (Leveraging Brain Insights)

While researchers explore cutting-edge treatments targeting neural pathways, individuals can take practical steps informed by neuroscience to manage tinnitus effectively:

- Reduce Stress: Engage regularly in practices like mindfulness, yoga, or meditation known to calm the nervous system and reduce activity in stress-related brain circuits (limbic system).

- Use Sound Therapy: Employ white noise machines, apps, or nature sounds to provide alternative auditory input, reducing the contrast and perceived loudness of tinnitus by engaging auditory pathways constructively.

- Maintain a Healthy Lifestyle: Support overall brain health through a balanced diet, regular aerobic exercise (improves cerebral blood flow), and adequate quality sleep (crucial for brain function and emotional regulation).

- Seek Support & Consider CBT: Joining a tinnitus support group or engaging in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) can provide emotional relief and teach cognitive strategies to change the brain's reaction to tinnitus, even if the sound itself persists.

Looking Ahead: The Future of Tinnitus Research Focused on Neural Pathways

The understanding of tinnitus neural pathways is a rapidly evolving field. Future research is likely to yield even more sophisticated approaches:

- Gene Therapy: Targeting genetic factors that might predispose individuals to auditory damage or maladaptive plasticity, potentially repairing damaged auditory cells or pathways at a fundamental level.

- Neurofeedback Training: Refining techniques that allow patients to visualize and consciously modulate their own brain activity related to tinnitus, essentially retraining brain networks through guided mental exercises and real-time feedback.

- AI-Powered Diagnosis and Treatment: Utilizing artificial intelligence to analyze complex individual data (brain imaging, auditory profiles, genetics) to create highly personalized diagnostic subtypes and design adaptive treatment plans (e.g., fine-tuning sound therapies or neuromodulation protocols) for optimal effectiveness.

Conclusion: Harnessing Neuroscience for Tinnitus Relief

Tinnitus is far more than just an auditory annoyance—it is a complex neurological phenomenon deeply rooted in the intricate workings of the brain’s neural pathways. By understanding these connections involving auditory processing, neuroplasticity, emotional centers, and attention networks, researchers are paving the way for more targeted and effective treatments. From neuromodulation and advanced sound therapies to potential future interventions like gene therapy and AI-driven personalization, the future holds immense promise for those living with tinnitus.

For now, combining currently available evidence-based therapies (like CBT and sound therapy) with healthy lifestyle adjustments that support brain health offers the best approach to managing tinnitus effectively and reclaiming quality of life. With continued research and innovation driven by neuroscience, the phantom noise of tinnitus may indeed become a manageable condition, or perhaps one day, a relic of the past.